Berthoff, Ann E. “Paulo Freire’s Liberation Pedagogy.” Language Arts, vol. 67, Apr. 1990, pp. 362-369.

“Paulo Freire is difficult to read because he is both a Christian and a Marxist—and those lexicons are sometimes at odds with one another. His theory, as I will try to show, is extremely important to us and so is his remarkable practice” (362). ***I am reminded of Bizzell’s skepticism about Freire, her “disillusionment”? And how much faith plays a part in any humane educational endeavor. And how this nature of humanity, its ability to learn, requires the lightest touches, the heaviest self-control on the part of the teacher.

Sometimes when I read this, I feel the power of it. I feel the terrible inclination of the American University towards acculturation, consumer-breeding:

He invented or reclaimed a method as old as Comenius; he taught the recognition of sounds and letter shapes simultaneously with meanings of some importance. But that is not why his slide projectors were destroyed, his primers burned – with the help of the CIA; it was not the fact that he taught literacy which sent him into exile. It was that his method transformed his learners so that they found a voice, which in this context does not mean a psychological event of self-realization but a revolutionary move away from the “culture of silence” toward naming and transforming the world. The agency of this transformation is what Freire calls conscientization and it is my hope that in what follows I can make that idea accessible. (362)

One of the things I just absolutely love about this article is that, like many things Berthoff, she employs “close reading” as a method; this enacts her methodology, because “how we construe, is how we construct.”

“I will focus on this statement from Pedagogy of the Oppressed: Dialogue is the encounter between men, mediated by the world, to name the world. I offer a close reading” (363). **I think of Rickert’s ambiance and the shared “strong emphasis on situatedness, interaction or feedback loops, affect, and the strong materiality of places and things” he values in the “fields” he chooses to explore, thinking with the notion of ambiance (Ambient Rhetoric 11). Freire and Berthoff do not dismiss situatedness or “strong materiality of places and things.” But they do keep a focus on humanity within these considerations. Both launch their philosophies from the argument, animal symbolicum, a move that acknowledges the differences in humans that make available the particular philosophies foundational to Freire and Berthoff. There is much resonance between Rickert and F & B. But, as with Heidegger and Cassirer, perhaps, there is a genuine rift in values. Here’s an interesting tidbit (from a pedagogue’s point of view…): Hans Sulga’s review of Gordon’s Continental Divide: Heidegger, Cassirer, Davos (2010). Now here’s a book I’d like to read sometime… I found this while seeking a tiny understanding of the relationship between Cassirer and Heidegger, a gesture of which happens in Berthoff’s “A semiotic journey across the field of Geist,” from Semiotica (1998). Notice this passage from Sula’s review:

At the core of their debate [Cassirer and Heideggar’s] at Davos (and, it turns out, at the core of their entire philosophical thought) lay, as Gordon puts it, “a fundamental contest between two normative images of humanity,” (p. 6) a contest “between thrownness and spontaneity” (p. 7). Where neo-Kantian Cassirer saw human beings as gifted with a capacity for “spontaneous self-expression” and thus endowed with “a complete freedom” to create worlds of meaning, Heidegger envisaged them to be determined by their “finitude” and thus as living in the midst of conditions they have not created and cannot hope to control. These are certainly important categories for characterizing Cassirer’s and Heidegger’s work.

I wonder to what extent this distinction might characterize Berthoff and Rickert’s orientations, and more importantly how this figures into their pedagogical philosophies and approaches.

I guess what I’m thinking is this… a Heideggerian approach to materialism and ambiance shrinks people in situations; people become subject to forces outside of their control. A Cassirerian approach focuses on people as situations in situations. That’s what triadicity does for us; allows us to articulate the complexity in ways dyadic notions of representation just can’t. But I have only superficially read Heidegger as yet. And I only know Cassirer via Berthoff. So… all this hopeful guessing…

Back to Freire…

Wait… If this is all about teaching, and relationship between teacher and student, language and thought, environment and human… then I vote we give new attention to Berthoff and the school of triadic semiotics, those who focus on the person in material context as a means of constructing methods that speak to the complexity of being and meaning.

“Paulo Freire’s pedagogy at every point recognizes that there is no direct access to reality: all that we know, we know by means of a mediating representation” (364). ***Experience, for us, does not happen without thought, and thought is mediated via symbol (word, image, sound….?), the mind in action, via imagination.

“Freire never dichotomizes language and thought, nor does he set them in anti- thesis to action” (364). **This is allatonceness. Notice thought and language are not cast in dialectic.

“The philosophical source of Freire’s conception of experience is existentialism, but it is also consonant with John Dewey’s ideas of education and Louise Rosenblatt’s theories of reading. (Indeed, Paulo Freire’s phrase “reading the world, reading the word” could serve as a subtitle for Rosenblatt’s Literature as Exploration” (364).

“The first activity of those in culture circles is to name the world of their village. They collect the names which represent what is important in their lives. These are the “generative words”: they are represented in visual form, they are discussed and renamed. Freire’s “generative words” are like Sylvia Ashton- Warner’ s “key vocabulary” and, when she writes that they are “the captions of the dynamic life itself,” we can hear the resonance with Freire, if we remember that for Ashton-Warner, no Marxist she, language is a social product” (365). ***Culture Circles and “generative words”

“Nobody had to teach anybody to do that – how to recognize a difference in a sameness; nobody had to teach you how to re-name. Children learn language by re-naming the world metaphorically. What we do teach – what we provide occasions for learners to discover – is THAT they are so doing, THAT they can re-cognize and re-present and re-name, THAT they can name the world” (365).

“Knowing THAT you know is what Freire means by conscientization. It is the process by which one becomes the subject of what one learns, a subject with a purpose which can be represented, assessed, modified, directed, changed. Conscientization means discovering yourself as a subject, but it is not SELF-consciousness; it is ‘consciousness of consciousness, intent upon the world'” (365).**You could just as easily say “object” here instead of “subject” and meaning would be the same. That’s interesting….

Interesting note on 365: “Freire’s method deploys a sophisticated understanding of linguistic analysis. The ‘generative’ words are so called not only because they generate questions but because, from the analysis of their phonetic structure can be generated [by] other words, by means of the ‘card of discovery.'” This reminds me of what English people do all the time (well, not all the time) when we identify the latin or french or german roots within a word. But the difference is in why we do it, which informs how we do it. Usually, English teachers offer language roots for the purposes of teaching spelling or “vocabulary”; students are intended to consume the material, memorize it, recognize it, associate it in a specific way, so that they can conform to determined, assessable “standards” for spelling and “vocabulary” purposes. Older students sometimes are offered roots as a place for building and supporting arguments when interpreting texts. Sometimes. But none of this work is “problem posing” work. It is all current-traditional, banking model teaching.

A note about “process” here: Just because you’re teaching that writing is a process, doesn’t mean you’re not teaching a ‘banking model’ method of teaching! In fact, I’d argue that most of us are still doing this, or mostly this (not an all or nothing situation), even though we identify as “of course” “process pedagogues.”

Conscientization entails bringing student awareness to the fact that they make meanings all the time, and how they do that, so that they can problematize the signs that form and convey those meanings. “Problematizing” is a much-abused term. It’s a Freirean term. It means to question that which we take for granted as inevitable—our words, the phonemes that compose those words, our signs. It means to question the context of the meanings we consume, create, convey.

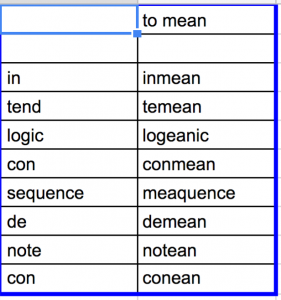

OED: † mean, n.1

Conscientization means…

Its purpose is a sociopolitical one, aimed at the individual in context/in time. To teach “process” of any form of language use, divorced from the pedagogical imperative of conscientization, is to teach a different kind of process than the distinct one espoused by both Berthoff and Freire, and, I will argue, Montessori.

“‘to exist humanly,” Freire writes, “Is tuning in the world, to change it. Once named, the world in its turn reappears to the namers as a problem and requires of them a new naming.” Thus it is that Freire’s learners are not problem sovlers but problem posers. In their renaming, they are “problematizing their existential situations”(366).

“When people learn that their misery and suffering are not necessary, that they are not God’s will or the inevitable pattern of Nature, their liberation has begun. Naming the world, speaking a true word, thus becomes the model, type, for cultural action for freedom” (366). ***I’m not sure what she mean’s by “a true word” here. But there is a hopefulness expressed in the articulation of “cultural action for freedom” here that moves me.

“The capacity to differentiate social conditions which are determined politically from those determined by natural necessity is developed from a deep resource, namely the power of recognition and the power of representation. Freire’s accounts are filled with moments of recognition. These epiphanies do not come from heaven, dawning on the solitary, alienated consciousness: they are dialogic…”

“The distinction between history and nature figures prominently in Marxist theory, of course, but MarxistsDo not always understand that the capacity to make that distinction is linguistic in origin and character and operation. The capacity to differentiate the conditions of our lives which we are free to change—our mortality and, generally speaking, our gender—this capacity is made possible by the imagination, ‘the prime agent of all human perception’ to use Coleridge’s phrase, and by the heuristic or generative power of language” (366).

“The human capacity to know that we know is exercised in the activity Freire calls conscientization, and concientization is essential to the pedagogy of knowing, which is how Freire characterizes education” (366). ****This passage is really key to understanding Berthoff’s appreciation for Freire’s focus on language.

And THIS passage is key to understanding what threads Berthoff/Montessori/Freire: “To take up Paulo Freire’s slogans without his philosophy of language will be to misapprehend his philosophy of history. Propounding the pedagogy of the oppressed without its philosophical moorings will be no different than settling for that alimentary education which Sartre make fun of: “Here, eat this! It’s good for you!” What we teachers of English need to know about Paulo Freire’s philosophy of language can be represented by what he said at the University of Massachusetts on another occasion:

Systematic education cannot be understood as a lever of transformation. The act of learning to read and write has to start from a very comprehensive understanding of the act of reading the world, something which human beings do before reading the words. These are moments of history. Human beings did not start naming A! F! N! They started freeing the hand, grasping the world.

‘Dialogue is the encounter between men, mediated by the world, to name the world” (367).

*****Here there is a recognition of what comes before naming. This is a person’s physical body Being in the world. Being comes first. And this is true for Montessori. Her way of employing materials in a classroom harnesses the act of “grasping the world” for the purposes of guiding learning. Her methodology nods to the natural primacy of being in the world (she teaches writing first), she has students name their environment (names are culturally/socially received) and invites them to write the names, place the labels, recognizing… This is what it means to build on what you already know (a student builds on what she already knows)…

” But familiarity breeds contempt– or at least boredom. What we must do is to become tramps of the obvious.We must look and look again at what we think we are doing when we substitute discussion for lecturing, assign what we think of as relevant topics, turn our students loosing the community to do oral histories, and so on. Whatever we might do to adopt Paulo Freire’s theory and practice to our own courses and curricula will be unsettling: he speaks of an unquiet pedagogy” and that’s what we tramps will have” (367). **I guess this is what Harris means by tendentious???

“I have elsewhere claimed that that is a hermeneutic insight: To see each person as representatives of humanity is, I believe, centrally important if we are to assure that interpretation is at the heart of all learning. If we read Freire alongside Schleirmacher, the fatehr of a general hermeneutics (a theory of interpretation),…Both are teachers who see teaching literacy as a hermeneutic enterprise, a vision of a humane society.” ***I don’t get it.When did hermeneutics to die? Did Derrida kill it? Foucault? And why? Wasn’t it working? Was it working at something else? Was it a problem? I don’t understand this yet.

“The prophetic church proclaims and then enacts the doctrine of the brotherhood of man; It recognizes that man is a spirit; It invites each person to recognize that he or she is representative of humanity. That is what it means to become a subject, as Freire says. It is a subjectivity which is realized in a social context and made possible by reason of our species specific powers of language” (367). ***That’s gorgeous. Makes a case for Freire’s work built on the same principles as triadicity.

“Liberation pedagogy could free us from fashion and fads – the foolish rush to whatever the educationist-publishing complex is beating drums about. Liberation pedagogy can defend us against the hostile demands made on us by a public duped into thinking that “a nation at risk” can be saved by screaming, “Accountability!” or “National curriculum!” (368).

“I heard nobody say, ‘But we must do what they say!’ The energy went into thinking, ‘If we are to do this, here’s how we must go about it in order to be true to what we know is possible and just'” (368).

“Teachers must work work work to see to it that cultural lit-

eracy is not equated with lists of facts to be digested. Literacy without conscientization can transform neither human beings nor their world. In liberation pedagogy, reading the world and reading the word are correlative and simultaneous. We have no more important a mission, no more creative a task, we teachers of English, than assuring that unity of literacy and a ‘consciousness of consciousness, intent upon the world.’ Paulo Freire has the last word:

Human beings did not come into the world only to adapt themselves to the situations they find. It is as if we received a mission to re-create the world constantly. This is human existence. By being historical beings, we are creative beings.

(369)

Damn.

I’m done.

I took the red pill.

Leave a Reply